Thomas Cole, Oxbow

![[grand-canyon-colorado2-1.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgdk5YNexLy7979CCrVQa9CA6MWpmlwc6gF69K-p3A1gRPpWV2VVYiBjSptTARQF2GmmUvHK3UNC8QRjztINJ1hSwmdVY-cAiFTd59zfO80btRsQcTWJ_C5rJpHrA6fKjJ8TuhpsndNm2P2/s1600/grand-canyon-colorado2-1.jpg) (left) William Henry Jackson (right Thomas Moran)

(left) William Henry Jackson (right Thomas Moran)The Hudson River Artists inspired young landscape photographers who were sent out West on exploration campaigns or geological surveys. The landscape photographers, like the Hudson River School painters, were simultaneously wowed and struck by the American Landscape. In fact, photographer William Henry Jackson (his photograph pictured above) actually worked alongside Hudson River School trained artist, Thomas Moran. Together Moran and Jackson created American desert views that seemed too large for any human life.

Wet Plate Collodian Illustration

Landscape photography in the late Nineteenth Century was cumbersome. Ambitious photographers practiced Wet Plate Collodian, a complicated procedure that was invented by the British scientist, Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. The Wet plate process, like the Calotype process, produced a negative, rather than a positive, but unlike the Calotype, it rendered remarkable detail. Unfortunately, the plates needed to be prepared, exposed, and developed while wet. Hence, field photographers, like Jackson, O'Sullivan, Muybridge, and Watkins, traveled with caravans packed full of chemistry, plates, darkroom supplies, light-tight tents, and cameras. Wet Plate photographers carefully coated their glass plates in makeshift field-darkrooms. The Collodian solution was a thick, viscous material, which was made from combining cotton gun, alcohol, and ether. The solution was then poured over the plate until it was tacky. Next, the plate was plunged into a light sensitive silver. Once exposed, photographers made positive prints, called Albumen Prints. The Wet Plate process was popular from the 1850s through the 1880s.

Timothy O'Sullivan

In the late Nineteenth century, photography became a popular exploration tool. Americans were still trying to understand their country and their identity. The United States, not yet one hundred years old, was not fully developed. The American west was still mysterious and new. Photographers made pictures to document the land, aid geologists and explorers, record railroad development, and archive the history of western expansion. Although most photographers at the time did not intend to make "Art," their pictures often exhibit keen sensitivities to form and aesthetic.

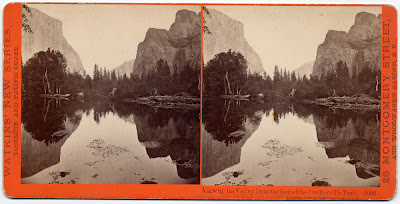

Carlton Watkins, Sterioscope (popular 3-D image card)

Muybridge, Yosemite Valley

William Henry Jackson

No comments:

Post a Comment